|

Note from Merrell Davis: [This is] the story of my two cousins J.H. Frasier who grew up in Marble Falls and Vernon T. Williamson, also from Marble Falls. It is an incredible story of survival for 3 years, 4 months as a P.O.W. on the part of J.H. Vernon lost his life as a P.O.W. aboard the Japanese transport ship Arisan Maru when sunk by the U.S.S. Snook (unaware that it was carrying 1800 P.O.W.s). Both were in the Battle of Corregidor (small Island of Corregidor). a siege that has been described as an "Alamo-like stand only 100 times over". Their bravery and sacrifice should make the citizens of Burnet County proud. J.H. taped his story and I transcribed it. History of the event and the ordeal of the P.O.W. experience under the most cruel captors in history was inserted to parallel and document J.H.'s story. The story is copyrighted and [JoAnn has]... my permission to put it on the Burnet Genealogy site. |

|

(Historical maps, history commentary, family-related photos, pertinent and explanatory medical information inserted. Remarks in parentheses while J.H. Frasier was telling his stories, identify other voices or sidebar comments during the taping. J.H. resides in Marble Falls, Texas with his wife, Judy, and many other close relatives and friends; near his roots and the Pleasant Valley family cemetery where his cousin Vernon T. Williamson's marker has been placed next to Vernon's parents) |

(J.H. Frasier taped account-- transcribed by 1st cousin Merrell Davis)

Some Family History.

Amanda Davis (J.H.'s grandmother), she was married to Jim Davis (grand-father James William Davis). They had three boys and a girl. Oran and Othal, --no, four boys. Malcolm and Damon and one daughter Lura (J.H.'s mother married to Amiel Frasier, J.H.'s father). My mother and Dad lived in this area (Marble Falls, Burnet county, Texas) all their lives. (They) never did go anywhere much (owned farm at the historical site of Morman Mill Pool, approximately 900 acres).

I recall Donna's grandfather (Grandfather of Donna was James T. Williamson, father of Vernon Williamson, who died as a POW on the Japanese Hell ship&emdash;the Arisan Maru with 1800 other prisoners when sunk by the USS Snook on October 24, 1944. 1200 miles south of the Formosa Strait---20 degrees 31' N., 118 degrees 32' E--- South China seas) running an ice house. He lived here in Marble Falls. He ran an ice house here and everywhere he went (also was Sheriff of San Saba, TX). That was the kind of business he was in. I don't know about California (Jim and family moved to San Francisco, CA during the war). He was a big, huge man. He would take a block of ice, I don't, I think they weighed 100 pounds. And he would take one in each hand. He was a huge strong man and that's my relationship with (him).

He was married to a Bible, Ora Bible. They had several children. They had Vernon, and Valma, Hilda, and Aretta, that was the youngest daughter. That was Donna's mother.

Getting back to myself. I was born and raised in this area. I graduated from high school in 1938. That was prior to WWII. Soon as I got out of school, I went to a business college for about a year. But it never came into much benefit to me until I got out of the service.

Basic Training and Going to Manila.

In 1940, '41, I volunteered to join the Marine corps. And that was the fighting in England, Germany and France---were involved in the war overseas in Europe. I volunteered and enlisted in the service in June, 1941. I took my basic training, I enlisted in Houston and I got on the train in San Antonio, going to San Diego. It took about two days to go from San Antonio to San Diego. There was several of us on, the recruits. And it was quite a---we got rather big headed because we were classified as Marines. In a way we though we were kind a big shots.

So we got to San Diego. We got off the train, and there was a big Sergeant waiting on us. We found out we weren't such big shots afterall. He told us to "Line up! You've been kind of your own boss for quite a long time. Now you are going to be under my control. Whatever I say, goes, don't ask any questions."

So we had our basic training, quite an experience. I was twenty, about twenty years old. And we had our basic training there at San Diego. We bivouaced in tents there in San Diego at the recruiting station. It took awhile to get through boot camp, quite a lot of experiences. I haven't got enough time to tell it all.

Anyway we had some recruit officers, enlisted men, who spent some time in China. About the time we got ready to finish boot camp, there was a request for volunteers to go to China, Shanghai, China. They had repeated how cheaply you could live there, and our salary was $21 per month. You could live on that salary and have money left.

So without any leave home or anything, we were put on board to ship out of---we went to San Francisco. We got on a ship called the USS Henderson. We went. We realized that we weren't going to go to Shanghai after we got to Pearl Harbor. There seemed like there was tension in the air. That was before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. They seemed to be quite tense. A lot of people were aware of the situation, that what was happening better than we were really.

We was just a bunch of green-horned kids. And we got to the Philippines, got to Manila. We tied up there and they told us that we weren't going to get to serve in China. We would be stationed in MBs (Marine Barracks-Cavite Navy Yard). The Navy yard across the bay from the Navy. We went over there. It was like an old building, kind of. There was no air conditioning, but it was right on the bay. And I remember the China clipper use to land right there in front of our place. There was a space.

And I realized that I had a cousin over there, and he was on Corregidor. But I didn't get to see him until the war had been going on for several, couple, three or four weeks. We, ah, the war finally started. Pearl Harbor got bombed, and we knew right away that we would soon be next on their list to get bombed.

|

DEFENSE OF THE PHILIPPINES Committed to the defense of Corregidor and Bataan in the Philippines, the 4th Marines, along with other American and Filipino forces, finally surrendered to overwhelming Japanese strength on May 6, 1942. But the six months of stubborn resistance slowed the Japanese timetable of conquest and won time for the mobilization of American industry and manpower. As a stimulate to sagging morale, the Philippine campaign was equally important. Not since the Alamo had such inspiration been drawn from a lost battle. Though defeated, the American soldiers, sailor, and Marines, by their heroic defense against overwhelming odds, inspired their comrades in arms and the civilians back home to redouble their efforts for final victory. The 4th Marines arrived in the Philippines just one week before the outbreak of war. The 4th Marines orders were to defend the Olongapo Naval Station and the Mariveles Naval Section Base at the mouth of Manila Bay on Bataan, the peninsula forming the Bay's Northern side. Total strength of the regiment was only 44 officers and 772 enlisted men. "What we had was what we had in Shanghai and what the Marines in 1927 brought with them. These were rifles, grenades, 20 millimeters, machine guns, B.A.R.'s that were actually from World War I. And of course, a lot of our equipment at the time in Shanghai was used for school. We'd tear them down, put them together. Tear them down, put them together. That's what we had during the whole war, six months of war, was the old threes and some of them would shoot and some of them wouldn't shoot. Especially with the grenades that we had. We had a box of, I think, there were 10 grenades in a box and if you threw 10, maybe three would go off. And the rest of them were just dried up because they were never used." - Pete George After the Japanese Carrier task force used over 350 planes to inflict 3,581 casualties (2,403 fatally) at Pearl Harbor, a message was sent from Admiral Hart on December 8 at 0350 hrs. "Japan started hostilities, govern yourself accordingly." Moments later buglers sounded "Call to Arms" as half-dressed, half-asleep Marines scrambled to attention. Immediately the regiment went about creating defense positions with foxholes and setting up machine guns for antiaircraft defense. Air raid alarms came at frequent intervals during the first few days of hostilities. All proved to be false until December 10 when the Japanese decided to hit the Cavite Navy Yard. Three Marine-manned antiaircraft positions were located at Cavite: Battery A, Battery B, and Battery C. Each position defended with .50 caliber guns with a range of 15,000 feet. As the Marines watched 54 aircraft in three large "V" formations approach the yard, everyone was anxious to fire. The first wave in the attack missed everything but the water as did the second wave. The rest of the attack began to destroy the Navy Yard as casualties began to rise. Approximately 1,000 civilians were killed and more than 500 were wounded in the attack. On December 12th, seven Japanese Zeros followed a flight of PBY patrol aircraft back to the Olongapo Naval Station. The Zeros waited for them to land, and attacked at once destroying them all. Turning inland, they began to strafe the naval station as Marines fired back with everything from machine guns to rifles to pistols. The next day, 27 bombers appeared over Olongapo at 1155 and bombs began to hit the Navy Yard and the civilians in the town. No installations were destroyed but many houses in the town were attacked with 13 civilians killed and 40 wounded. The intended use of the 4th Marines in the defense of the Philippines called for the transfer of the regiment to Army operational control. General MacArthur decided to use the 4th Marines for beach defense on Corregidor. The defense of Corregidor was vital in the defense of Manila Harbor, a location of importance for the Japanese. In late December, all Marines in Cavite and Olongapo were to assemble together in Mariveles. Admiral Rockwell ordered a detail of Marines to destroy the Olongapo Navy Yard. All structures not blown up had to be burned down including the warehouse that held all of the footlockers of the 4th Marines. These footlockers held nothing but the best memories of Shanghai. Deep carved chests filled with ivory, jade, silk robes and photographs of the best duty in the Marine Corp. Four islands protected the mouth of Manila bay from attack. Corregidor, the largest island, was fortified prior to World War I with powerful coastal artillery and named Fort Mills. The tadpole-shaped island lay two miles from Bataan, and was only 3.5 miles long and 1.5 miles across at its head. This wide area, known as Topside, contained most of Fort Mills' 56 coastal artillery pieces and installations. Middleside was a small plateau containing more battery positions as well as barracks. Bottomside was the low ground where a dock area and the civilian town of San Jose was located. East of this was Malinta Tunnel, location of MacArthur's headquarters as well as a hospital. On December 29th, the 4th Marines got their first taste of aerial bombardment on Corregidor. The attack lasted for two hours as the Japanese destroyed or damaged the hospital, Topside and Bottomside barracks, the Navy fuel depot and the officers club. January 2nd, 1942 the island garrison was bombed for more than three hours. Periodic bombing continued over the next four days and with only two more raids in January, the regiment had a chance to improve their positions considerably. January 29th the Japanese dropped only propaganda leaflets which greatly amused the beach defenders. On February 6th, Japanese artillery opened fire on Corregidor and the fortified islands from positions in Cavite Province. The forts were shelled eight more days and bombed twice in February. Occasional shelling and bombing hit the fortified islands until March 15th when the Japanese began preparations to renew their offensive on Bataan. The bombing and artillery raids now continued unabated until the end of the siege. Typical bombardment would consist of two periods of shelling, beginning at 0950 and 1451, and six bombing raids beginning just after midnight and spaced throughout the day. On top of the bombardment was the dwindling food supply. The regiment was living on 31 ounces of food per day. Drinking water was distributed only twice a day but the constant bombardment often interrupted the ration. When the bombardment killed the mules in the Calvary, they would drag the carcasses down to the mess hall and cook them up. The continued lack of proper diet created major problems for the 4th Marines, as men were weakened and lacked reliable night vision. The regiment would not have a full meal until 3 years later. "We heard that the Americans are going to come over and they're going to bring supplies and replacements and all this and that which they never did. We never did see a ship. A submarine would get in there every now and then, but the ship, we saw one ship come steaming in and a submarine blew it up before it got into the bay. So we were without supplies, replacements, our food was running low, and, of course, we had C-rations and the Army had K-rations, and that dwindled away. They had the Calvary and started eating the horses, you know. They' butcher up the horses and pass that meat around and everything." - Pete George On April 9th Bataan fell to the Japanese after a final offensive broke through the USAFFE defenses trapping more than 75,000 men as well as several thousand Filipino refugees. By Christmas eve, MacArthur evacuated his headquarters in Manila and set up shop on the island fortress of Corregidor. The Japanese wasted little time before focusing their attention on Corregidor, intensifying their bombardment of the island the same day Bataan fell. The largest group of reinforcements arrived after the fall of Bataan, 72 officers 1,1173 enlisted men from more than 50 different organizations were assigned to the 4th Marines. Unfortunately, very few of the reinforcements were trained or equipped for ground combat. By the end of April, the 4th Marines numbered 229 officers and 3,770 men, of whom only 1,500 were Marines. Japanese bombing and shelling continued with unrelenting ferocity aircraft flew 614 missions from April 28th until May 5th , dropping 1,701 bombs totaling 365.3 tons of explosive. At the same time 9 - 240mm howitzers, 34 - 149mm howitzers, and 32 other artillery pieces pounded Corregidor day and night. It was estimated that on May 4th alone more than 16,000 shells hit Corregidor. On May 5th the Japanese boarded their landing craft and barges and headed for the final assault on Corregidor. Shortly before midnight, intense shelling pounded the beaches in-between North Point and Calvary Point. The initial landing of 790 Japanese soldiers were met by the 37mm guns of the regiment. In addition, the Japanese struggled in the layers of oil that covered the beaches from ships sunk earlier in the siege and experienced great difficulty in landing personnel and equipment. However the overwhelming number of Japanese infantry equipped with 50mm heavy grenade dischargers and "knee mortars" forced the Marines to pull back from the beach. The second battalion of 785 Japanese soldiers were not as successful. The invasion force did not prepare for the strong current in the channel between Bataan and Corregidor. This battalion landed east of North Point where the defensive positions of the 4th Marines were much stronger. Most of the Japanese officers were killed early in the landing, and the huddled survivors were hit with hand grenades, machine guns, and rifle fire. Some of the landing craft did however make it to the location of the first invasion force and found themselves moving inland enough to capture Denver Battery by 0130 hrs, May 6th. A counterattack was initiated to move the Japanese off of Denver Battery. This was the location of the heaviest fighting between the two forces, practically face to face. A few reinforcements did make their way to the front-line Marines but the battle became a duel of American World War I grenades versus the deadly accurate Japanese knee mortars. Without additional reinforcements, the battle would quickly go against the Marines. At 0430 Colonel Howard decided to commit his last reserves, the 500 Marines, sailors and soldiers of the 4th Battalion. These reserves tried to get to the battle as quickly as possible but several Japanese snipers had slipped behind the front lines to make movement very costly. Additionally a third battalion of Japanese troops landed around 0530, adding 880 fresh reinforcements for the Japanese. The 4th Marines were holding their positions at the same time losing ground in other areas. The Japanese were facing problems of their own, several ammunition crates never made the landing. Several attacks and counterattacks were fought now with only bayonets. The final blow to the 4th Marines came about 0930 when three Japanese tanks landed and went into action. The men around Denver Battery were ordered to withdrawal to the ruins of a concrete trench a few yards away from the entrance to Malinta tunnel just as Japanese artillery delivered a heavy barrage. Realizing that the defenses outside Malinta tunnel could not hold out much longer and expecting further Japanese landings that night, General Wainwright decided to sacrifice one more day of freedom in exchange for several thousand lives. He was particularly fearful of what would happen were the Japanese to capture the tunnel where lay 1,000 helpless wounded men. Colonel Howard burned the regimental and national colors to prevent their capture by the enemy. About 1300, Captain Clark and Lieutenant Manning went forward with a white flag to carry Wainwright's surrender message to the Japanese. The survivors of the regiment were quickly rounded up by the Japanese and exposed to the status quo for treatment of POWs. Grouped together, shaken down for any noteworthy possessions, and humiliated as conquered subjects of the emperor. Casualties of the Marines for the entire Philippines campaign totaled 331 killed in action, died of wounds, and missing and presumed dead, and 357 wounded in action. The Japanese recognized that the five-month battle for the Philippines was seen by the world as a defining contest of wills between the United States and Japan. Lieutenant General Masaharu Homma, Japanese commander in the Philippines, recognized the critical nature of this conflict when he addressed his combat leaders in April 1942, saying:

The Allies would fight and die for 3 _ years to gain the release of these prisoners and put a stop to the Japanese killing machine. MacArthur's leadership in the Philippines was tactically wrong and showed serious errors of leadership. Knowing the facts of Pearl Harbor, MacArthur allowed his air force to be destroyed on the ground in one hour. His decision to disperse his troops and their supplies in order to defend the entire island, rather than strengthen all men and equipment to Bataan immediately, resulted in deplorable conditions among his troops. MacArthur's remoteness, egotism, self-aggrandizements, and distortions of reality alienated his naval commander and jeopardized the safety of his troops. Relief from his command should have been considered but instead MacArthur became a national hero to all except to the starved and disease-ridden men on Bataan and Corregidor. On the other side, Japanese Commander Homma who did conquer the Philippines in five months rather than the two months as projected by the Japanese Command was relieved of his command. |

Waiting for War.

So we just kept waiting for something to happen. And finally we had. The war wasn't declared. President Roosevelt declared war on Japan, and he. I remember him stating very well, he said, on one of those fireside chats. He said, "I want to assure all the mamas of the boys who are of age to be enlisted, drafted, that I will not declare war until we are attacked first." So that's what I knew when they attacked Pearl Harbor. So I knew that gave them an excuse to declare war. I had good sources of information saying the allied forces, American forces knew that the Japanese were coming before. They gave 'em a cause (to declare war on Japan) because they wanted it to look bad. It sure did.

So, ah, we were bombed there in, I don't remember the date. But it was the latter part of '41. We just moved out of the barracks, out into a tent area. We stayed there two or three nights, and everything was hectic, confusion. The Filipinos were going crazy. They thought they were being attacked with gas, by poison gas, which it wasn't. We had gas masks, everyone us had gas masks. And the Filipinos wanted to trade us for gas masks. We wouldn't do it.

|

Bataan was not synonymous with Corregidor, mistaken belief to the contrary. As a result of this belief, many have assumed Bataan, Corregidor, and the Death March to be interrelated. Corregidor had very little relationship with Bataan; it had no connection with the Death March whatsoever. Such a mistaken belief has been spawned by numerous writings. |

But anyway, we moved on up outta the area. All the lights at night we weren't allowed to burn, and everything was dark. They were in the midst of bombing attacks every few days. So we moved from MB navy yard around to Manila, and up to Mariveles which was across from Corregidor.

My cousin was still there in an battery on Corregidor and I hadn't seen him yet. I knew he was there. After a couple of weeks we moved over to Corregidor, my outfit.

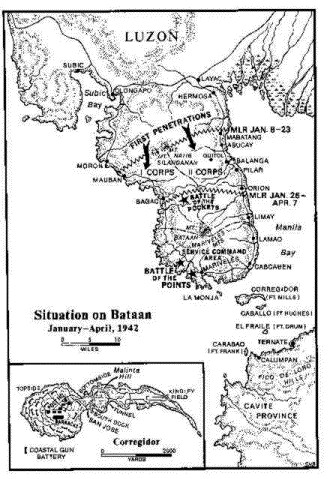

Details of the Situation on Bataan January-April 1942, including the area of first Japanese penetrations, Corps areas of responsibility, the Battle of the Pockets, and the Battle of the Points. Ft. Mills is located on Corregidor and this map represents one of the most detailed maps of the war zone known to exist. (CORREGIDOR NOW & THEN &endash; ECHOES IN TIME internet web site sponsored by Corregidor Historical Society <http://corregidor.org/ct&n_index.html>)

|

Under Fire and Surrender.

And everything, the war was really darn hectic. The bombing and artillery. The Japanese had taken out all of the, just about all of the Philippines. And about all the Americans had left was Corregidor. And so I was stationed on the lower side of Corregidor on the east side. Vernon was on the topside.

Finally on one Sunday afternoon when the war got ( ╔"I can't think of it", J.D. remarks to himself). I decided I would contact Vernon. I'd find out where Vernon was at, where he was located, and walked around our station over to where Vernon was (about a mile or so). And Vernon always was a messing with party guys. And he had a blackjack game going that had been going for a day or two. He took advantage of that. He had about 7, 8, maybe ten black jack games going with as many as he could get in each game. I came up and he was just as nonchalant---"Hi J.H., how are you doing?". And he was all business.

And finally we got to talking some. And he would rake the money in and take his cut out. Then divide it up amongst the ones that were winners. And like I told this one (Donna). I don't know what he did with all the money he had, but he had lots of money. I don't know what he ever done with it. That was the only time I ever saw him while the war (on Corregidor) was going on.

And so when, pretty soon, the war, Corregido surrendered. And that place was literally flattened out. You couldn't find not one living thing on that base, that had a sprig of any kind. It was formed, it look just like a floor, flat as a floor.

Anyway we, the ones that. Well when they surrendered, I was in an anti-tank gun outfit. I had an enclave on the side of a cliff that I had dug into the rock, parallel above the road. And I was to knock the tank out that was coming around before they surrendered.

I had this gun, the barrel was about 14 inches long, and it shot a projectile about the size (laughs) of a big shotgun shell. I was to knock this tank out with this little "BB Shooter". And so, just as I saw this tank coming around the curve about 100 yards off, somebody yelled 'Frasier' get your ass inside. We're gonna run up the flag, the white flag. Actually, if I fired that thing at the time, he'd blown me plum off the side of that mountain!

("How long where you bombed there before you surrendered?", Donna asks J.H.) Oh gosh, I don't know. It seemed like 2 or 3 months. It was 2 or 3 months. And we had, it was strange we had a bakery right out in the middle of all this that survived right up to the very end. Never even a fragment of anything ever hit that thing in all that time. The bakery there finally, finally they wiped it out.

We finally surrendered and they moved us to the end of the island of Corregidor. And we moved down on the bottomside, they called it. There was, I don't know how many thousands there was, but there were quite a number of us. We had no water, no food, no anything for quite awhile.

Then I managed to get together with Vernon along about that time. We stayed together off and on. We were there, I forget how long we stayed there without any food or water. But it was longer than you think anybody could live without any water or food. But you don't know what you can do, stand until you have to do it.

|

If Manila Bay, one of the finest natural harbors in Asia, was a bottle, then the Island of Corregidor was its cork. Whoever controlled Corregidor, controlled Manila Harbor. That was General MacArthur's theory and the Imperial Japanese Armed Forces, in defeating him on Bataan, proved him right with the capitulation of the Luzon Force on 9 April 1942. This sunburned, God-cursed land, where bombs and shells made life hell, with death on every hand denied the Japanese of all use of Manila base---until 7 May 1942, when the garrison surrendered after a dogged defense without air-cover. It was the scene of an Alamo-like tragedy magnified a hundred times over, and more than a third of the who were ordered to surrender would never survive their POW experience to see home again. The USN had 2100 men and the U.S. Marines, 1500 surrender with 175 officers included---not counting ally forces. |

Prisoner of War in the Philippines.

And so we finally, they loaded us. They never tell you anything. But they had that ship out there in the harbor for quite awhile. We thought we was going to get to go to Japan. That was our idea how to get out and away from there. So they loaded us all on the ship. Instead of going out to sea we went back toward Manila.

We pulled up, the ship pulled up to the dock, instead of letting us off at the dock. They let us off the ship on little barges. Instead of going up to the beach, they put us off into the water, about neck deep, and it, was over the head of quite a few. Several guys drowned, they hadn't prepared themselves to survive, couldn't swim in.

They lined us up on the beach, and they were great ones to put on airs. So they lined all these soldiers and marines, and sailors, and so forth upon the road, Manila boulevard. They had a big parade. You can imagine this parade. Their soldiers were riding on horseback, all dressed up in their fancy uniforms and everything. They paraded us through Manila. And it was kind of pitiful I guess. They moved us down to, the troops went in different directions. I was in a place called VillaVille. It use to be a hospital during the early years. I stayed there 2, 3 or 4 days. And then we were all guessing what was gonna be done next. Always rumours of some kind.

We were definitely feeling the effects of not having enough to eat along about then. They loaded us up on these box cars. It was real hot weather there, stifling hot. They loaded us up in box cars that they hauled their freight in, coals and so forth. They tried to get one hundred on each box car; fifty would have been a big load for them. There were men who had dysentery, sick, everything, they were just.

When they thought they had all that they could put in there---they would take their bayonets and punch you, you know and drive you more in, You could just barely stand. If you were unfortunate enough to get down on the floor there, of the car, you just stayed there. You usually didn't come out of there. They'd unload the car of the dead and all. (What part of the year was this?) That was in the early part of '42, along about April.

But anyway we were on this train for a day, I'd guess, something like that. Then we got off into this place, Kavanacuam (sp?). I told you about that. We got off. It was raining. I was still able to stand up and walk. We walked about, I don't know, must have been 3, 4, or 5 miles to the camp at night.

We got there and they had a place fixed for all of us. And there were places made out of bamboo. They were better than being out in the weather. But they didn't stop all of the rain from coming right in there.

Then I located Vernon again. He was in the same camp with me. He and I got together in the camp right there. He was in the same camp with me (momentarily distracted by questions for clarification). So we had an opportunity. A lot of them that died right there due to lack of food. Finally I was having trouble with my eyes. One Sunday afternoon, I was watching the ball game. Softball game amongst the troops. Amongst the prisoners. I had been seeing as normal as anybody. All of a sudden a curtain came down in front of my eyes, and I just went blind. Right there! I managed to get back to the barracks. I had enough vision to see, tell day from daylight from dark.

Anyway time moved on and my eyesight gradually came back a little bit (blind for approximately a year╔.caused by beriberi). It was called beri beri. I contracted a form of malnutrition called "dry beriberi". They had a form (wet beriberi), one of them was your legs and limbs would swell up. I've seen medics drain the fluid off the leg as big as a bucket. They had 2 or 3 gallons of fluid come off them. I never had that trouble, I had dry beriberi. Your legs didn't swell up but they got hot.

[NOTE: J.H. Frasier and cousin Vernon T. Williamson both suffered from life-threatening POW diseases and were amidst other diseased soldiers suffering from the same camp conditions described in the below account]

|

The men of the 200th and 515th Coast Artilleries (AA) who fought on Bataan during WWII were ordered to surrender to the Japanese by General Edward P. King, Jr. on April 9, 1942. They had fought a good fight for four months, and held off an enemy vastly superior in number and arms. When the Japanese captured the men on April 9, they were made to walk the "Death March", a 65 mile trek from Mariveles to San Fernando. The men of the 200th and 515th Coast Artillery who survived the "march" reached Camp O'Donnell in about eight to ten days only to discover conditions would worsen. They suffered from lack of nutrition, dehydration, and illnesses. Among the many diseases they contracted were Malaria and Dysentery which were the worst, but the men also suffered from Dengue Fever and Beri-Beri. During the three-and-a-half years in prison camps, the majority of the 13,000 deceased men died from disease. (Dorothy Cave, Beyond Courage, Las Cruces, NM: Yucca Tree Press, May 1992, p .155.) Malaria affected many of the POWs. The men would get chills, fever, and severe sweating. There was no way to stop the spread of Malaria since it was transmitted by mosquitoes and blo flies. The men would beg the Japanese for medicine, bandages, surgical equipment, cots, food, and bedding, but this would only anger them. The Japanese violated the Geneva Convention in not giving the POWs proper food and medicine. The meager rotten food the Japanese selected to give their prisoners only made these bedraggled men more ill. Huge blo flies would land on latrines and on their food, thus further spreading the diseases. (Donald Knos, Death March, Orlando, Florida: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1981, p. 161.) In Camp O'Donnell, there were hospitals of sorts. The men would get some medical attention and medication like "Quinine" which was used to treat Malaria. They got most of this through Black Market trading with the Filipinos or trading among the prisoners. Without medical attention, the POWs were left to fend for themselves or die. Often, their stomachs would swell, and since they had no medication, they would boil cactus and bind it to their stomachs; this would help the swelling go down. If the men were beyond help, they were taken to the "Zero Ward" where they were taken to die; here, no one was expected to live; they simply awaited burial. (Dorothy Cave, Beyond Courage, Las Cruces, NM: Yucca Tree Press, May 1992, p. 114.) Dysentery struck the POWs because there was no proper sanitation and no sanitized water. This bacteria enters the body through the mouth in food or water, human feces, or coming into contact with infected people. Dysentery causes inflammation of the large intestines; there is much pain, fever, and severe diarrhea accompanied with blood and mucus. (John E. Olsen, O'Donnell, U.S.A: John E. Olsen, 1985, p. 155.) The men had no control so their feces spread the disease to others. There were not many latrines available for the men, and the ones they had were disgustingly dirty, so they would often use buckets, or dig large holes or trenches and use them as toilets. For toilet tissue, the men used grass, sticks, and leaves. (Dorothy Cave, Beyond Courage, Las Cruces, NM: Yucca Tree Press, May 1992, pp. 210-213.) Dengue Fever and Beri-Beri also plagued the POWs. Dengue Fever is a virus whose infection is also transmitted by mosquitoes. After being bitten, the men would have a range of symptoms including fever, rash, and severe joint pain. Beri-Beri is caused by a deficiency of Vitamin B, which the men contracted from improper diet. With "dry" Beri- Beri, their feet would swell with sores. They tried to get their swelling feet to go down by putting them in buckets of ice water, if available; however, they would get pneumonia or diphtheria from which many died. With "wet" Beri-Beri, the men couldn't pass liquids, so they would swell; the liquids would work their way from their feet to the heart. When the liquid reached the heart, it put pressure on it causing it to stop beating. They had no medication for this so they would often slit their stomachs and draw the liquids out with a hose to relieve the pressure. (Dorothy Cave, Beyond Courage, Las Cruces, NM: Yucca Tree Press, May 1992, p. 225.) Malnutrition and disease were deadlier than the enemy was. Many men died from the diseases; however, the men who had them still wanted to live. They had faith that they would one day be set free and would return to good health. Some of these brave men, who overcame the diseases and tortures of their Japanese captors, did finally return home. Of the men who lived through this terrible tragedy, a third of them died from complications after returning home. For many survivors, their health was ruined forever, and for all of them, this nightmare is one they will not likely ever erase from their memories. |

Going to Japan, but Without Vernon.

So I still had the opportunity to volunteer to go to Japan. But you never knew for sure where you were going to go. You might volunteer to go to Japan and wind up somewhere else. Vernon and I both decided we wanted to go to Japan. But he had contracted Malaria in the mean time. We didn't have a hospital but we had a place across the road. There is where they sent the ones they didn't think could make it (Zero Ward). Vernon was still there in camp when I got ready to leave. He was going to go with me to Japan but he had this malaria and wasn't able to go. I managed to get hold of some quinine that saved his life. He managed to live during almost through the whole complete war. He never did get to go out. But I'm sure he managed to get quinine while there.

(Did he, were you ever able to see the Red Cross? Donna asks J.H.) Ah, we had an opportunity during the 42 months I was there. We had an opportunity to get a Red Cross parcel; about twice as big as a shoebox and had different items. I got one and a half. The Japanese took those. I got a package from home and had a pair of khakis. I got a sweater (from Mom and Dad) and a pair of khakis, vitamins. That was about the size of it. I got these quinine for Vernon, I pulled him through that. I never heard from him for a long time. He managed to get through, get over that malaria. We went back to Manila, and I couldn't hardly walk on account of my feet hurting so bad (symptoms of dry beriberi). I couldn't wear any shoes. So I walked the night we left out; it was about 8:30 or 9:00 (p.m.) we left out. We left out, the road was muddy and it was real hard to walk. So we got back on those cars (train boxcars) again. They wasn't, wasn't quite as big of a load, loaded as before. We went to Manila and we stayed two or three days. We got on this ship. There was about 1500 of us on this ship that was, that was ah; normally be a full load is 500. Then we got on the ship. We thought maybe they let us roam around on the ship. But they put us down in this, in the hole where it was just the lid on it. And that was something else!

That was after we, when we left Manila. They put about 1500 of us, Manila to Tokyo. It was really kind of barbaric in ways. We always looked forward to someone dying off so it would give us more room. You didn't have much patience, you didn't have much sympathy. But anyway, I managed to survive. We got to Taiwan. There was a harbor there. The maggots, the lice, the bed bugs, everything was bad and it was pitiful.

They got us off the ship, lined us up on the dock. Stripped our clothes off and washed us down with salt water, right out of the ocean. That was about September, something like that. They issued us a pair of shorts and a short sleeve shirt. That was what we had to face with winter.

But it felt good to get a bath, get rid of them bugs for a little while, except those that you had on your head. But anyway, finally we got to Japan---but first, backing up a little. We'd been on our way about a week. Somebody hollered out, says "torpedo attack, submarine". We were torpedoed by a submarine but they missed us. The ship captain managed to navigate the ship where it missed that ship, that torpedo. So they were just (So it was one of our ships that torpedoed the ship that you were on? asked Donna). No they weren't trying to torpedo (us---American POWs). They didn't know what, they had put on a little war supplies and everything on there; some of their troops on it.

But they didn't have the ship marked. But that was what happen when Vernon got it. Their ship wasn't marked. It should have a Red Cross or something on it. And he'd be here today.

We got to, seem like it was Labor Day, we got to, I don't know, it was Japan. It was pretty cold then, compared to what we had. (Pause).

But anyway, we got off the ship. We were so glad to get there and get off that ship. We all lined up on this kind of grade there. And it was pretty, cold there; and all we had was a pair of shorts and a short-sleeved shirt. And we thought well, we've had worst than that. So finally that night, they put us on this train.

It was such a relief to get some heat, you know some warmth. We went on there for a while. It was your normal passenger train. Pretty soon after we got on the train, they came around serving us this meal. They gave us a box of food. It looked like a cigar box. It had some rice and seaweed, and you'd be surprised what they can do with that seaweed. But anyway, seaweed, some snails, things like that. But it was awfully good whatever it was. That was about a good of meal I ever had. It took about 6 or 8, 10 hours to get to Tokyo. We got off the train. We walked over to the place we were going to stay.

This was a place that had been made out into the bay, little bit of grassy (sp?) wood. They channeled out, let it pile up a little, and let it settle. So (used) it for cover like an island. We were quite awhile and I still having this trouble with my feet. And there was no medication, nothing. Couldn't even get aspirins for your problems.

Conditions in Japan.

It started getting winter time pretty soon. And my feet began to really give me a problem. I couldn't hardly walk on them. They were red as they could be from the heat, the temperature (Your feet were burning from the Beri-beri?). Yeah, they were burning good. (?) came up and he puts your feet into a pan of water, ice water and wouldn't take no time it would be like it (water) had been in a stove or something.

I slept with my feet out from under the covers. We had a little bit of covers. (What kind of shelter did you have there?) Oh it was just regular barren-like place. Dirt floors and they have be fifty on one side, on the ground floor certain times. Fifty on kind of a little hallway down the middle. Then on the, they would have a double-decker, and there's no heat. And it gets pretty cold there in the winter time. Snow and everything.

We had a, finally they put me and another little boy, an Englishman. He lost his, both legs just about a foot below his knee. They had finally rotted off. We had one guard. We were in, they put us in a place called, kind of a, considered to be a, they couldn't understand you know. They had never had problems with that. They thought really that we were kind of odd to them. Because they couldn't feature anything like that happening to anybody. (Did that happen to a lot of the men?). Not a lot, no. But they did have quite a lot of them who had arms, legs, body swell up. Beriberi, yeah. All it was, was nutrients, malnutrition.

We had a guard, he kind of felt sorry for us. I'll never forget, he'd bring us, they were three or four of us, suffering like that. He'd bring us a little opium when he would come on. (Really!). Yeah. And that was, you talk about---it was really, I mean you could get use to it. You didn't care whether the sun rose or not. You just, give you so much pleasure you know. You get rid of the pain for awhile. (Low discussion, unintelligible).

(Side two continues)

(Did you give him anything?) We didn't give anything. He just felt sorry for us. Finally they sent me and another or two over to a hospital. They called it a hospital. Shinigawa they called it, the name of the base. Suppose to have been a part of the military. But actually what it was, just a kinda, we were kinda guinea pigs over there. They took us over, we thought it an old (?). They put us in rooms with high ceilings. There were little doors, little windows at the top. No beds, just slept on the, had a kinda mattress we slept on the floor. We'd get the regular rice and, if you had the dysentery; that's real bad bowel trouble. They gave you charcoal, mashed up charcoal. If you ever get dysentery, try that, it works. (Laughter). But this is funny.

Frozen Feet

We got a little better food, maybe, than we did at camp. But I had this trouble with my feet. My feet finally kinda starting pink. They were frozen. They turned pink, then they turned kinda blue and then they turned black, they turned black. I had a piece of an old sheet that I managed to make into a bandage, into a bandage. I had two of them. I'd use one of them and wash the other one. I noticed these flies kept buzzing around my feet down there. I didn't care because they were bugs. I didn't care what they was doing.

So one evening I went down going to see the doctors or nurses would work on them. I had to wait on myself. I took the bandage off my feet. And Lordy Lord! there's all these places on there where that old flesh and everything had died. There was where the maggots were. And they cleaned that just as pretty as anything you ever saw. So the (?) my toes, I couldn't get anybody to take them off. So I just managed to work them off myself. I dropped them in the latrine (the whole toe!) I never had as much as an aspirin the whole time I was there.

Refused to Take Shots

They were giving some of us a shot in the groin here. Then taking pictures, so they were going to find out what was causing the problems. So nearly everyone they gave a shot to, died. So it came my turn to get a shot, (laughter). I told these guys they may give me a shot but it will be the last one they ever give me. So I told them so. So I told them I'd refused when it came my turn, and I caught hell from all the other troops there.

They said you're going to mess our good thing up here by refusing to do this. I said, "I'm not going to take a shot. I don't care what they do."

So it came my turn, they got me in the place. And I said "No there are no shots. And they told me two or three times. I didn't know what they were going to do to me. They tell you, and finally no, okay. So (?). They didn't give us anymore shots after that. (Did you ever find out what that was?) I don't know what it was. It was a normal injection, a needle. It was about the size of a match, maybe a little bigger, half the size of a pencil. And it had a bunch of enough stuff in it to fill a half of a fruit jar, (Really!). And some of 'em took up and died very soon after they got the shot. I told them that I'm not having it. I was a big hero then after awhile (Laughter&emdash;tell them about the box your father sent you and the tooth powder adds J.H.'s wife.).

Oh, so in the box my dad and mother sent. There was a box of Colgate tooth powder. You know normally you would use that for your teeth. Well, that came early so I thought well I'll try to save something for Christmas. So I saved that powder for my rations.

But the worst thing in Tokyo was fleas. They had a sand flea. That actually, oh gosh you can't imagine how they would get on you at night. We had a sheet that we made a bunk out of, and trying to fix it where they couldn't get in. But they were the, that sheet would look like a, "have you ever seen a turkey egg?"---but it had spots all over it. And where that sheet was. You never get adjusted to them bites. I mean when they bit you, you knew you'd was bit. Wake you up at night. Everybody was, and you see them under you around on the floor and everything.

Forced Labor

Well now, another story I want to mention to y'all. They'd send these guys that were able-bodied. I never did work on the outside on a job. But those that did go on the details outside; they would go out and work on ships, unload ships. They did more damage to the ships than they did to anything else. They jammed their gears, they sabotaged them. They be unloading sugar and things like that, and rye and they managed to get home with it. And finally for a long time they got to bring that in and distribute it out amongst the men. But they'd get caught occasionally (How were they╔.). then they would get literally the hell beat out of them. They'd be beat to where they wouldn't know where they was hardly. You'd be surprised how much punishment a human being could take.

I never really had any problems about that. I wasn't able to do much. I was working there in camp with a, making like I couldn't half see. I was separating pieces of leather. Goat hide, that was used to make covers for the mess kits, stuff like that. We were sitting in this old building and at an old table. There were about 8 or 10 of us in there. We had the windows up. And this Jap guard would sit up front there he'd, oh like this. We saw this old red hen come outside there. We watched, we said "wouldn't it be nice to have an egg?".This old hen flew up in that window and she flew right over into the pile of stuff we was working on. Sat right there. We whispered to ourselves "Don't make any noise." Some of them didn't know what an old hen would do.

Right before they lay their egg, they cackle! So someone was detailed to watch the hen; and whenever she laid the egg, but as soon as she laid the egg---grab her; take her to the window and sling her out the window.

Can you imagine an old hen like that! And she came there for about ten or twelve times. Every day she'd lay an egg there; and we cast lots to see who would get it, take turns---and that old Jap guard never did know the difference. Can you imagine an old hen treated like that! Come right back every day. That was really something!

Freedom

(When were you all freed? How long after the bombing of Hiroshima were you all freed?) It was about a week or so. We knew right away whenever they, ah. That is just about (thinking to himself), I might mention that they kept telling us that they could last for years and years. But they began, along toward the end---we never knew exactly what was going on. But they finally started having air raids, and the B-29s. They would come over. They'd have air raids that would come at night.

|

Allied POWs were spread out all over Japan, small camps of only 500-1000 men. Outside the camps, the Japanese population was eating miserably and the POWs were hardly eating at all. The POWs knew they had to slow down on their work details or they would never see the States again. By the end of 1944, the emperor of Japan knew that the war was lost but he encouraged his commanders for one final victory so that he may dictate the terms of peace. The emperor would never agree to unconditionally surrender, a decision that cost Japan millions of lives. The Allied push to recapture strategic islands in the Pacific put Allied bombers within reach of Tokyo. POWs were beginning to hear and experience the bombings from the new B-29 Superfortress. These massive planes were delivering a payload of 4-5 tons, with air raids lasting several hours. The early months of 1945 began with a different method of aerial attack, incendiary bombing. Modern Japanese cities were constructed mainly of wood and Japan's war-making capabilities would soon be burned to the ground. Along side any industrial district is heavily populated civilian areas. The industrial center of Tokyo had more than one million people living and working in a twelve mile area. The night of March 9th of '45 saw the biggest air raid in history to that date, 279 B-29s turned Tokyo into a solar flare. Temperatures as high as 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit turned buildings into blast furnaces, cars simply melted and civilians disappeared. This single bombing raid burned sixteen square miles of Tokyo, 80,000-100,000 Japanese died, 40,000 Japanese burned and a million left homeless. Still the emperor would not surrender unconditionally. The fire bombing continued and by the end of June, 13 million Japanese were homeless. The B-29s were dropping bombs at the rate of 40,000 tons a month and all major industrial cities were left in ashes. A naval blockade completely surrounded Japan and on July 25th, the Potsdam Declaration had warned the Japanese that if they did not surrender unconditionally, their country would face 'prompt and utter destruction.' Japan was defeated but the emperor chose to ignore the declaration. Allied commanders knew that an invasion into Japan would be one of the costly events in the history of warfare. When the tiny island of Corregidor was recaptured, five thousand Japanese defended for eleven days to the death and only twenty were taken prisoner. The atomic age began on August 6th, 1944 when a single B-29 dropped "Little Boy" on the city of Hiroshima. The city was leveled in seconds and one hundred thousand Japanese were dead. One factor that favored Hiroshima as the target was the fact that Allied intelligence said there were no POWs in the city. For most of the POWs, liberation did not come in a formal announcement from the camp commander. Instead, work details were cancelled and the guards gave excuses explaining why there would be no more work details. The POWs knew the war was over when American fighter planes and bombers began appearing overhead, thousands of seabags and 55-gallon drums full of food, clothes, and cigarettes were parachuted into the camps. In just seconds, the POWs finally had a full stomach after 3 1/2 years of starvation. However, the POWs were still being held by the Japanese and a nervous tension began to settle in with the prisoners. One of the most painful feelings the POWs had to endure the length of the war was never knowing what the Japanese were going to do next. Based on what they experienced with the Japanese, it would not have surprised any of the prisoners if the guards started to massacre each and every one of them. For many of the POWs, they were told that they were going to be moved to another camp, they boarded trains and trucks and were driven to American forces. Now, finally the POWs knew they had survived and were going home. |

We had hope. Now that was the thing. If you gave up hope, then you'd die because there's nothing else to live for then. But every day was the end of the war, see, and you'd go day by day. At first you'd say, well, we surrendered in May and by Christmas the Americans are going to be here and get us out. Of course they never made it so then it would be the 4th of July and then it would be Christmas again. So it just kept you going all the time. . . . Oh, gosh the feeling that you had, boy, was just like somebody had 10,000 pounds on your shoulder and all of a sudden it was lifted. You were just elated that you were free and, people just don't understand that if you don't have your freedom, what it really feels like. It's just-- it's just bad. That's all it is. It just holds you down and everything else. And boy, from then lifting that weight and knew that the war was over with and that we were free and that we were going -- that we were going to go home and boy, you were just -- your smile was just moving your ears away. You know, in other words you're smiling so wide, you know, that it was really something though. --- Pete George

Web site source "4th Marine Regiment &endash; Liberation" <http://www.chinamarines.com/docs/lib.htm>

I remember one night it was snowing. They had an air raid about 2 o'clock (a.m.). These airplanes was coming over; they began dropping their bombs. I don't know how they could tell where we was. But there were never any bombs that hit the Americans. They'd drop those bombs and like they thought it so bad, you know; about the atomic bomb. Well there was more damage done by those incendiary bombs than the atomic bomb did; of any long lasting effects. You could see fires as far as you could see. They'd drop those things; as soon as they contacted they blew up. (discussion)

Finally they moved me up to a place they called Sindine (sp?). That was about half-a-day or so ride by train up in the mountains. There was a stream of water, river up there. And they had a mine up there. I forget if there was any copper up in there.

It was in June, I believe it was June. We went up there. There was snow up in the mountains. And we thought well its sure going to be rough here this winter. Because we didn't have any heat. It was just like an old barracks, old barn. It was new though, the whole place was new.

Sure enough those Japs they kept telling us they're going to be able to hold out for another ten years. That we could win and all that stuff. Finally one day, the troops had all gone out that morning, took the working party out. They come back about noon. The old Japs were, they were really downhearted. They didn't bother us, didn't give us any instructions, didn't tell us anything.

Finally, they called a meeting and got up on a platform. Told us that Japan had surrendered. We were there about a week, something like that. It was over with. We got to leave and go back to the States.

We got aboard the hospital ship. Lord howdy!, we really went after that food. The best thing we had to eat was homemade bread, like bakery! Nearly everyone when they'd go by the bread line; we were told, heck I can get anything you want, as much as you want! I get a whole loaf. The bakery people were going crazy---they couldn't keep the bread. I knew people who were skinny and I went from about 100 pounds, I guess. I got down to 85 pounds one time; but going from 100 to about 165 pounds in less than 6 weeks out. That's about the size of it.

But I came back. I finally found out what happen to Vernon. ... [Photo of Vernon Williamson and condolence letter]

Lists of POWs on-board the Arisan Maru when she departed Manila, October 10, 1944. She was torpedoed on October 24th. All but 8 or 9 men of the 1800 on board lost their lives.

Source: Arisan Maru roster list from "4th marine Regiment -- Liberation" site: http://www.chinamarines.com/docs/lib.htm

[Photo of Arison Maru]

Came back to the United States. I didn't get to fly back.. Some of them flew, got to fly back. I didn't, I came by ship. Took a couple of months to get home. I knew uncle Jim (Williamson). I talked to my mother on the phone (Arrived at San Francisco port and disembarked there). She told me that uncle Jim lived there. (San Francisco).

END OF TAPED ACCOUNT BY J.H. FRASIER (March 2001)

Note by Merrell E. Davis, cousin of J.H. and Vernon, who transcribed taped account from J.H.:

J. H. Frasier told me at the Double Horn reunion in Marble Falls, Texas that upon his return, he caught a cab and located his Uncle Jim's home. During the visit, there were many questions and especially any knowledge about Vernon. J.H.'s uncle Oran W. Davis was an USN Lieutenant and had gone to greet him upon his return but failed to find him. While visiting uncle Jim and answering their many questions---Uncle Oran approached the front door and J.H. met him at the door, pleasantly surprising Uncle Oran. They later that day took a photograph together at a photo studio.

[Photo of J. H. Frasier with his uncle Oran W. Davis] [Photo of J. H. Frasier and family at his homecoming]

|

Prepared and written by Merrell E. Davis on 23 February 2003 to honor J.H. Frasier by transcribing his taped account mailed to me as part of documenting the Davis Family genealogy. Copyright [c] 23 February 2003 Merrell E Davis. Several sources were used and identified on the history of the Island of Corregidor WWII battle between the Ally (Americans, etc.) occupying force and the Japanese Imperialist Army between April 9, 1942 and May 7, 1942; including period of time before and after (POWs of Japanese until they surrendered). If anyone reading this material believes there is a copyright violation, please notify me at <2nightowls@cox.net>. This advisement is to protect the content from being pirated by unscrupulous persons desiring to utilize it as their own material. ( a growing problem on genealogy sites). |